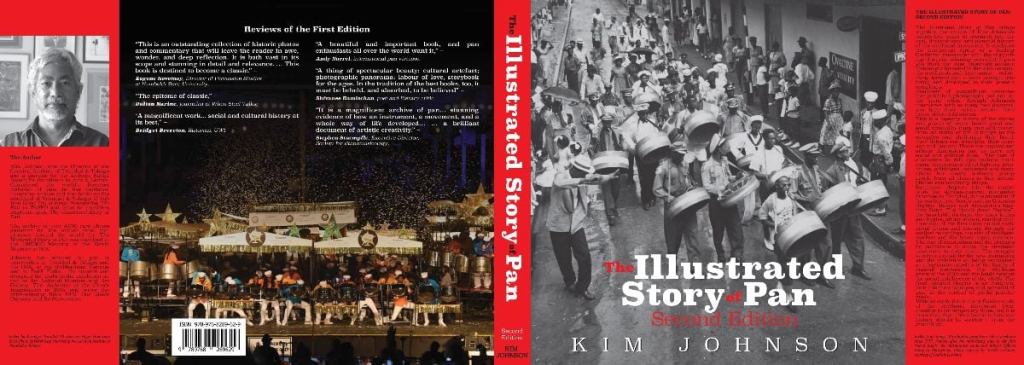

There is this thing about books on the steelpan and the steelband movement. They are sometimes large books with plenty words. There are not that many books though; certainly, less illustrated coffee-table sized books have been written on the steelpan than on the electric guitar for instance, or the piano The thing is, Kim Johnson, pan researcher and author of this new book, The Illustrated Story of Pan, has already written three of those large coffee-table sized books. And to make matters worse for the idea of the proliferation of pan publications, he wrote the first edition of this book a decade ago in 2011. There is still a lot of work to be done. This new edition is updated with never-before-seen photographs, new ideas, clearer editorial. It is a renewed celebration of that “audacity of the Creole imagination,” as he brilliantly describes the steelpan, which one would be remiss not to have on their shelves.

Caribbean pride aside, having a book like this is a “must-have” for music lovers, for people curious of the “other”, for people looking for an exploration of the worlds outside the centre, for people looking to populate their “shelves as furniture and decoration”! Derek Walcott told us in his poem The Spoiler’s Return: “…as for the Creoles, check their house, and look / you bust your brain before you find a book…” Don’t be that guy! Get the book.

Kim Johnson uses a phrase for the title of the first chapter of this book, “The Archaeology of Memory”. This is where I intersect with him. Some years ago just after the launch of the first edition, I showed Johnson a few photos that my late father took in 1961 of some kids playing those early instruments as a kind of entertainment or frolic at our house. Next thing I knew, I saw the picture at a lecture he gave on early pan. At that point, I knew our paths would cross again, as he formally requested to use the photos in this second edition. Pride and place is given to Danny Campbell’s photos of a memory lost to me, but not to time.

Kids playing early pan in Trinidad, circa 1961. Photo by Danny Campbell

That is the power of the photograph over the written word. No matter how well constructed a sentence is, in my mind, it can not eclipse the proof of concept, the certainty of memory, the captured reality of a photo. Even if there were no words in this book — there are many, and all well written to capture a perspective unseen by many foreign researchers — the photographs in this book tell a story. An almost linear history of the evolution of pan is revealed, and the familiar exercise of seeking stories to go with images that many do with old family photo albums — or in modern times, photo and video sharing social networks — allows one to go into the world that created the steelpan.

What was termed by a writer as those “urban yards, those laboratories of sweat and spit and fire,” where steelpans were created and nurtured become the backdrops for a visual narrative that suggests that there were also social situations, people and politics that melded to form a movement and an image that is more than the cliché of the Caribbean in those vintage Caribbean travel posters — a barefoot wide-brimmed hat wearing native playing a pan-round-the-neck.

Images and words here place the steelpan forward on the arc of musical instrument development in the 20th century and puts into context its place in the history of Caribbean independence and self-determination. We see in this collection of photographs, which is by no means an authoritative canon or an official source, and we read in the well researched and attested words, the power of determination to be more. A Caribbean circumstance of stolid repetition of Colonial manners — the Haitian Revolution and other smaller slave and labour rebellions aside — has marked our slow march to modernity and to self-sustaining normalcy in the 21st century. The steelband movement and the instrument’s evolution as determined by the pan people, celebrated characters and forceful figureheads who are all shown in this book, have taken that slow road to maintaining a dogged and sustained presence.

Creole audacity brought to the world an instrument and a movement, a community that removes barriers of race and class, importantly at a time of celebration of the West Indian brio. The denigration of past authors and travel book writers — VS Naipaul in The Middle Passage reminisced infamously, “the steel band used to be regarded as a high manifestation of West Indian Culture, and it was a sound I detested” — is superseded by the majesty given to the steelpan and the steelband in the words of and in the collation of memories by Kim Johnson here.

Memory, audacity, determination are celebrated in this book. Inclusion, too, that has allowed for modern jazz, world music and folk musicians to take the steelpan sound to a wide global audience. The timbre that resonates as a relaxing tone for meditative minds can also move masses to chip and jump and celebrate in our unique way. The Illustrated Story of Pan, Second Edition is the unravelling of all these parts that make the steelpan and the steelband movement significant and possible. If this book inspires long time pan people, limers, panmen, flagwomen, panyard crawlers all to tell their stories, to build those memories, to learn the instrument’s history, it has done a good job. If it inspires a new generation everywhere to take pride in the continuing evolution of Creole audacity, it is well worth the purchase.

© 2021, Nigel A. Campbell. All Rights Reserved.

Comments

After reading the book review: Illustrated Story on Pan, Second Edition, by Kim Johnson, I proceeded to purchase the book on Amazon. I was unsuccessful. Amazon explained that the book is currently unavailable. Hoping that the book will be available on Amazon soon.

The Illustrated Story of Pan is available at https://www.santimanitayblog.com/theillustratedstoryofpan